Why Some Days Feel Sharp - Part I: Your Biological Night

Sleep quality depends on structure, not hours. Most people build that structure backwards.

Introduction: Why Some Days Feel Sharp

Some mornings you wake up clear - focused, steady, energetic. Others feel blunted and sluggish. For most of the past year, I woke up feeling like a zombie. I slept, I tracked, I hoped the next night would fix things, but it didn’t.

So I started taking my energy levels very seriously. I pulled 488 nights of sleep data from my Oura ring (bed/wakeup time, duration, heart-rate curve, consistency, recovery). Then, over three months, I tracked what I could precisely control: fluid and caffeine timing, meal composition and timing, and exercise. Light, temperature, routine, environment were not variables - they stayed stable. The variables that moved were behavioral, and measurable.

I thought at least one of these variables would be the answer. It wasn’t.

They all influenced sleep. But their impact depended on something more fundamental: whether the structure underneath the night was aligned with my body’s recovery window.

Your body has a biological night - a specific window when deep restoration actually happens. It’s not about sleeping “enough hours” or “at the right time” in isolation. It’s about whether three structural elements are working together:

Regularity: whether your body can predict when the night will happen

Timing: whether your sleep lands inside your biological recovery window

Duration: whether you’re giving the aligned structure enough time to complete

When these three layers work together, you wake up sharp. When any one breaks, nothing else fully compensates.

How do you measure if you’re aligned? I needed something simpler and more direct than Oura’s readiness score, which blends too many inputs: activity load, heart rate variability (HRV) balance, sleep debt, temperature. It’s useful as a general summary, but it obscures the specific mechanism I was looking for: circadian alignment.

I used a single metric:

Alignment = |Sleep Midpoint – HR Nadir|

Where:

Sleep Midpoint = the center of your sleep period (halfway between when you fall asleep and wake up)

HR (Heart Rate Nadir) = the time your heart rate hits its lowest point during the night (the deepest part of your biological night)

The smaller the gap between these two moments, the better your sleep window overlaps with your body’s internal recovery cycle. If you sleep from 11 PM to 7 AM (midpoint: 3 AM) but your HR nadir happens at 5 AM, you’re misaligned by 2 hours. You’ve started sleeping before your body was ready for deep restoration.

This metric isolates timing from everything else. It doesn’t care how long you slept or how much REM you got. It just asks: were you asleep during your biological night?

A note on the data: This analysis is based on 24 months of sleep tracking (488 nights with complete data) using a Generation 3 Oura Ring, plus 3 months of detailed behavioral tracking (caffeine, fluids, meals, exercise). This is an N=1 study with consumer wearable limitations, but the principles are established science.

Across the data, one pattern dominated everything else. Sleep quality depended on a structure that had to be right before anything else mattered. Three levers shaped that structure, and they formed a strict hierarchy:

Regularity sets the rhythm.

Timing lands you on that rhythm.

Duration matters most once the first two are working.

Underneath all of that is a fundamentally important signal: light. One big driver around your body predicting when night is coming is through light exposure patterns. Regularity works because it creates consistent light/dark cycles. Timing works because it aligns your sleep with the darkness your body has learned to expect. Recent research suggests that controlled light exposure can shift circadian phase by 1–2 hours in a week (though it markedly has some flaws). overriding even sleep schedule changes. I didn't track light directly, but the principles above likely work because they produce consistent light patterns. So, naturally, exploring light is a promising new experiment - specifically answering the question "how fast can I adjust my circadian rhythm with strict light interventions?”.

Caffeine, meals, fluids, and exercise all affect sleep. But when the underlying structure was misaligned, optimizing those variables felt like rearranging deck chairs. Once I fixed the foundation - regular timing, adequate duration - everything else started working the way it should.

This is Part 1: the foundation. The other parts (caffeine, fluids, light, meals, exercise) will come next.

Finding 1: Regularity Sets the Rhythm

Your body is a prediction machine. Give it a consistent schedule, and it starts preparing for sleep before you even get into bed. Take that consistency away, and the entire recovery cascade delays by nearly an hour.

What I Mean by “Regularity”

Regularity isn’t about rigid bedtimes or perfect discipline. It’s simpler:

Regularity: how consistent your sleep and wake times are from one day to the next.

In sleep science, this is measured with the Sleep Regularity Index (SRI), which captures how often you fall asleep and wake up at roughly the same times each day. A high SRI means your circadian system gets consistent inputs. A low SRI means every night looks like a different schedule.

What matters is not perfection - it’s whether your body can predict the night.

Prediction is what makes the nightly descent into recovery start on time.

The Body Needs a Predictable Night

What surprised me most wasn’t any single habit - caffeine, fluids, exercise, meals. It was how much the body depends on prediction.

Your circadian system is a learning machine. It observes when sleep typically happens and begins preparing a few hours beforehand: core temperature drops, melatonin rises, sympathetic activity (stress) falls, parasympathetic (relaxation) tone increases. This “wind-down cascade” doesn’t wait for you to decide to sleep - it starts based on when the system expects sleep.

When your schedule is consistent, the cascade starts on time. When your schedule drifts, the body loses its anchor and the descent delays itself.

This is why regularity matters: it gives your internal clock a stable target. Without that target, every other aspect of sleep becomes more volatile.

How Irregularity Shifts the Physiology

If regularity truly shapes recovery, the signature should appear in the systems that follow circadian timing most closely. Heart rate is one of them. It tells you when the body settles, how quickly parasympathetic activity rises, and when the internal night reaches its depth.

I wanted to see if irregular nights delayed that entire process.

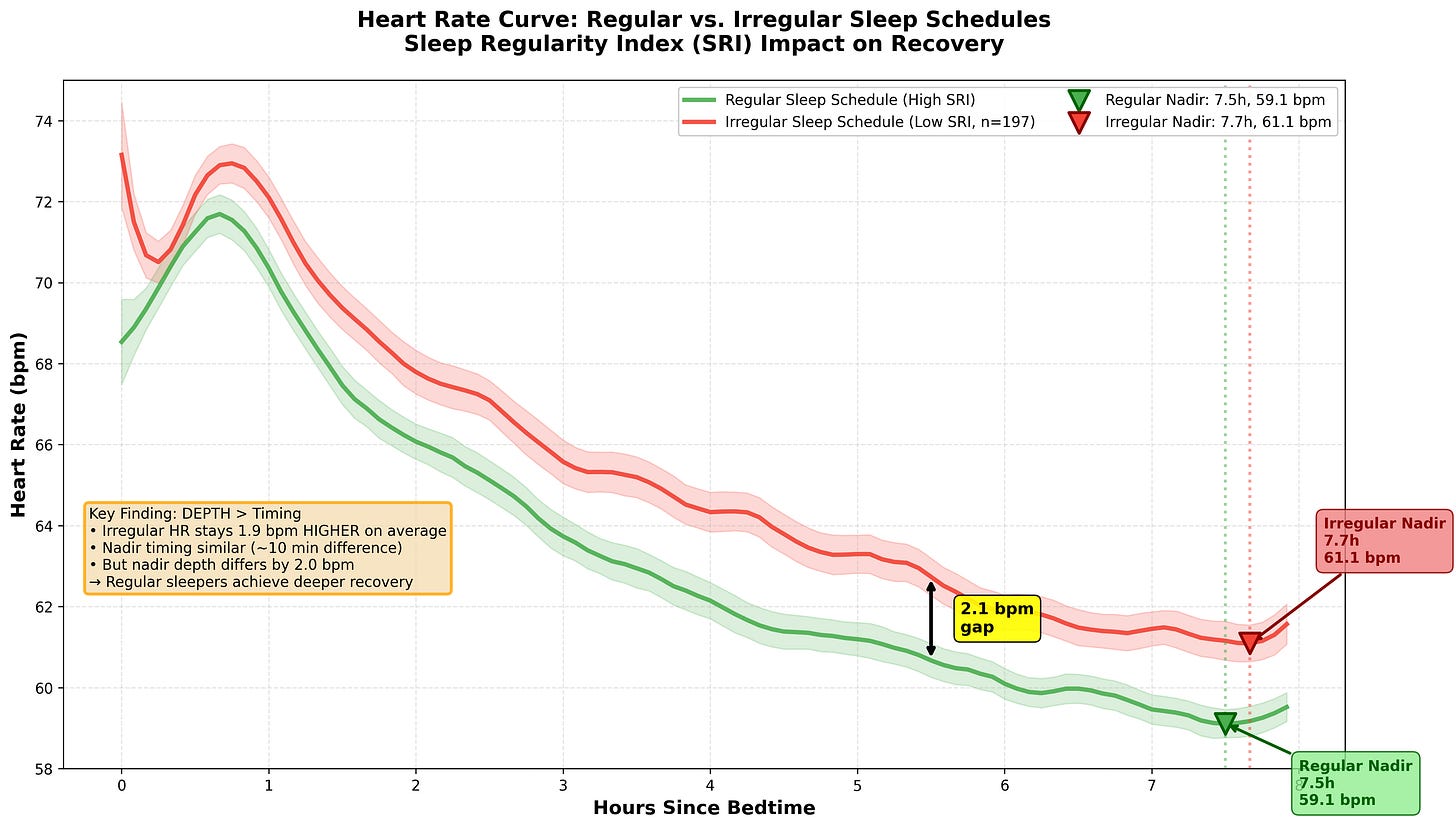

So I averaged every night’s heart-rate curve and aligned them by sleep onset. The difference between regular and irregular nights showed up immediately.

On regular nights, the curve followed a clean arc: a small rise in the first hour, then a smooth, predictable slide downward toward the night’s lowest point.

On irregular nights, the entire curve sat higher, and everything happened later. The drop started later. The nadir arrived closer to 7–7.5 hours instead of 6.5. Even the early-morning rise shifted. That’s nearly an hour delay in reaching peak recovery - not because the body is broken, but because it’s still preparing for a night it expected to come later.

The difference wasn’t subtle: regular nights (n=228) showed a nadir at 6.5 ± 0.8 hours after sleep onset, while irregular nights (n=197) showed a nadir at 7.3 ± 1.1 hours (difference = 48 minutes, p < 0.001).

Nothing catastrophic happened minute-to-minute, but the whole night ran slightly behind. The body wasn’t misbehaving; it was preparing for sleep later, because the previous nights had taught it to expect the night later.

Regularity → prediction → timely physiological descent → better recovery.

Irregularity breaks that chain.

Figure 1: Overnight Heart-Rate Curves by Regularity.

Regular nights show an earlier, smoother HR descent and earlier nadir. Irregular nights shift the entire curve later and higher.

What a Stable Rhythm Looks Like in Practice

To quantify my own regularity, I calculated the Sleep Regularity Index (SRI). My median score was 43.8, splitting the dataset almost evenly:

228 nights in the “regular” range

197 nights in the “irregular” range

My median SRI of 43.8 was well below the research benchmark of 85, indicating my sleep was genuinely irregular. This wasn’t by choice - it reflected the problem I was trying to solve. My schedule wasn't chaotic. But even these modest variations - shifts of 45–60 minutes - were enough to move the entire heart-rate curve.

That’s the point: regularity doesn’t need to be perfect. It just needs to be reliable enough that your body knows when the night is coming. Once that anchor is stable, the nightly descent starts on time, HR drops smoothly, deep sleep appears earlier, and the rest of sleep unfolds predictably.

The practical takeaway: you don’t need perfection, you need predictability. Shifts of 30–45 minutes won’t destroy your sleep. But swings of 2–3 hours will teach your body that the night is uncertain - and it will stop preparing on time.

Give it a rhythm it can trust, and the rest becomes easier.

Regularity gives your body a predictable rhythm. But that rhythm has to occur at the right time. A consistent 2 AM bedtime is better than an erratic 11 PM bedtime, but a consistent 11 PM bedtime that lands inside your biological window is better than both.

Which brings us to the second layer: timing.

Finding 2: Timing Lands You on the Rhythm

Sleep from 11 PM to 7 AM is not the same as sleep from 2 AM to 10 AM, even if the duration is identical. Your body has a biological night - a specific window where deep restoration actually happens. Miss that window by an hour, and recovery weakens dramatically.

Your Biological Night Has a Real Clock Time

Once regularity gives the system a stable beat, the next question is: when should that beat occur?

Note: some cutting-edge research suggests

Your body doesn’t treat all nighttime hours the same. Sleep from 11 PM to 7 AM is not necessarily the same as sleep from 2 AM to 10 AM, even if the duration is identical. There’s a window - a specific span of clock hours - where your physiology is primed for deep recovery.

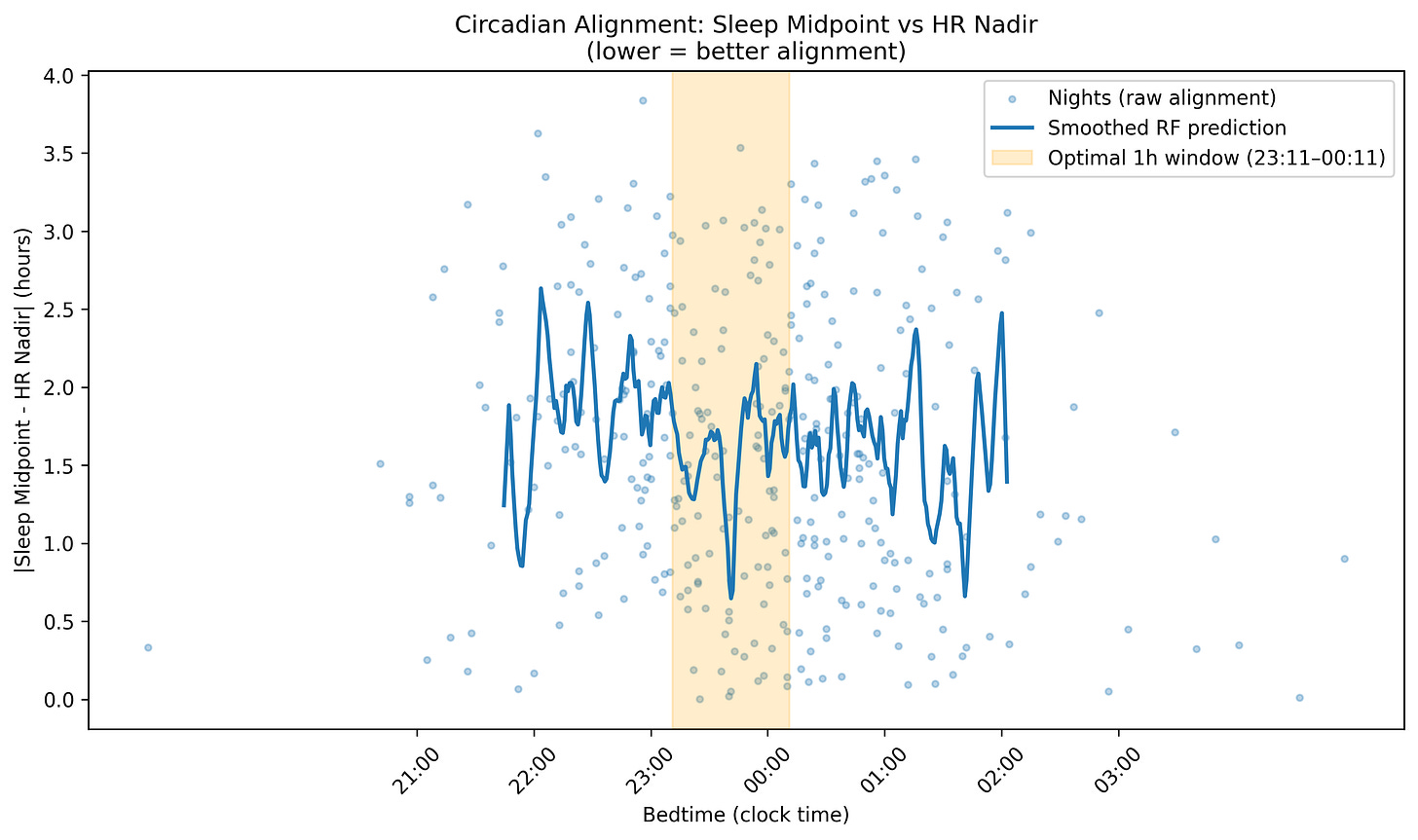

You can see this window in the Figure 2. It’s centered around one landmark: the HR nadir - the lowest point your heart rate reaches overnight. That moment marks the deepest part of your internal night, when core temperature bottoms out, melatonin peaks, and parasympathetic activity dominates.

A note on measurement: The gold standard for measuring circadian phase is core body temperature minimum, but that requires lab equipment. Heart rate nadir correlates strongly with temperature minimum (typically within 30–60 minutes) and is what consumer wearables can actually measure. It’s not perfect, but it’s a good proxy available for tracking your biological night at home.

When your sleep midpoint falls close to that nadir, the whole night runs smoothly: early deep sleep, clean heart-rate descent, strong HRV rise. When your sleep midpoint drifts away from the nadir - even by an hour or two - the physiology drifts with it.

It’s not about sleeping “early” or “late.” It’s about sleeping when your system is already prepared to restore you.

Figure 2: Circadian Alignment Curve.

Lower values mean sleep midpoint and heart rate nadir were closer together. The highlighted window shows the 1-hour bedtime range that minimized misalignment. For me that was ~11:30PM.

Sleeping in the Window vs. Missing It

I wanted to see what happened when I hit that window consistently versus when I missed it.

Across the data, the strongest recovery consistently came when sleep began between 11:11PM and 12:11AM. This was my window. Yours might be 11PM to 12AM, or 9:30PM to 10:30PM, depending on your sleep chronotype. (For step-by-step instructions on finding your own window using a wearable, see Appendix A.)

Why Windows Differ Between People

Your biological night is set by your circadian clock - controlled partly by genetics (clock genes like PER3 and CLOCK) and partly by long-term patterns of light exposure, meal timing, and sleep schedules.

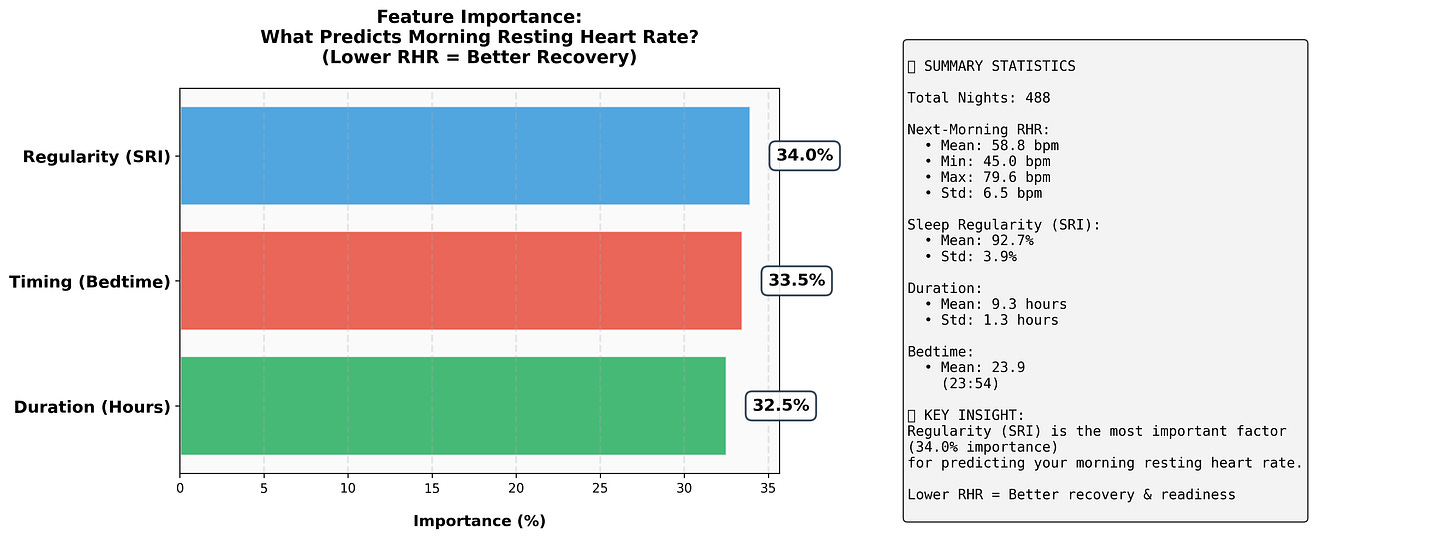

Figure 3: Feature Importance of Sleep Variables.

Among sleep-hygiene factors, regularity predicts recovery most strongly, followed by duration and bedtime. Timing matters - but only once consistency is in place.

"Morning people" have internal clocks that run faster than 24 hours and naturally phase-advance - their melatonin rises earlier, their temperature drops earlier, their biological night starts earlier. "Night owls" have clocks that run slower and naturally phase-delay - everything shifts later.

You can't completely override this with discipline. A night owl forcing sleep at 21:00 (9 PM) is sleeping before their biological night begins - the sleep happens, but restoration doesn't.

But chronotype is more malleable than traditionally assumed. A controlled light intervention study found that both early and late chronotypes shifted their circadian phase by 1–2 hours (!!) in a single week using morning bright light and evening light restriction, with no significant difference in how the two groups responded. The system is trainable. Other research suggests that work schedules and lifestyle factors measurably influence circadian timing, reinforcing the idea that your window is shaped by environment, not just genetics.

That said, these shifts required strong, consistent light signals. Blue light glasses for 2 hours upon waking, orange-tinted glasses for 3 hours before bed. Real-world shifts without controlled interventions will be slower. You can meaningfully nudge your rhythm, but I am dubious of turning a true night owl into a 4 AM riser. (For strategies on shifting your window when it conflicts with your schedule, see Appendix B)

The principle is the same for everyone: find when your body naturally hits its lowest resting point at night, and time your sleep so the middle of the night lines up with it.

What Happens When You Miss Your Window

When I slept inside my window:

Heart rate dropped quickly

Deep sleep arrived early

HRV rose smoothly

Alignment stayed tight

Mornings felt clean

When I slept outside that window - even for the same number of hours - recovery weakened. Heart rate fell more slowly. Deep sleep shifted later. The nadir crept toward morning. Readiness dropped.

Then something unexpected showed up.

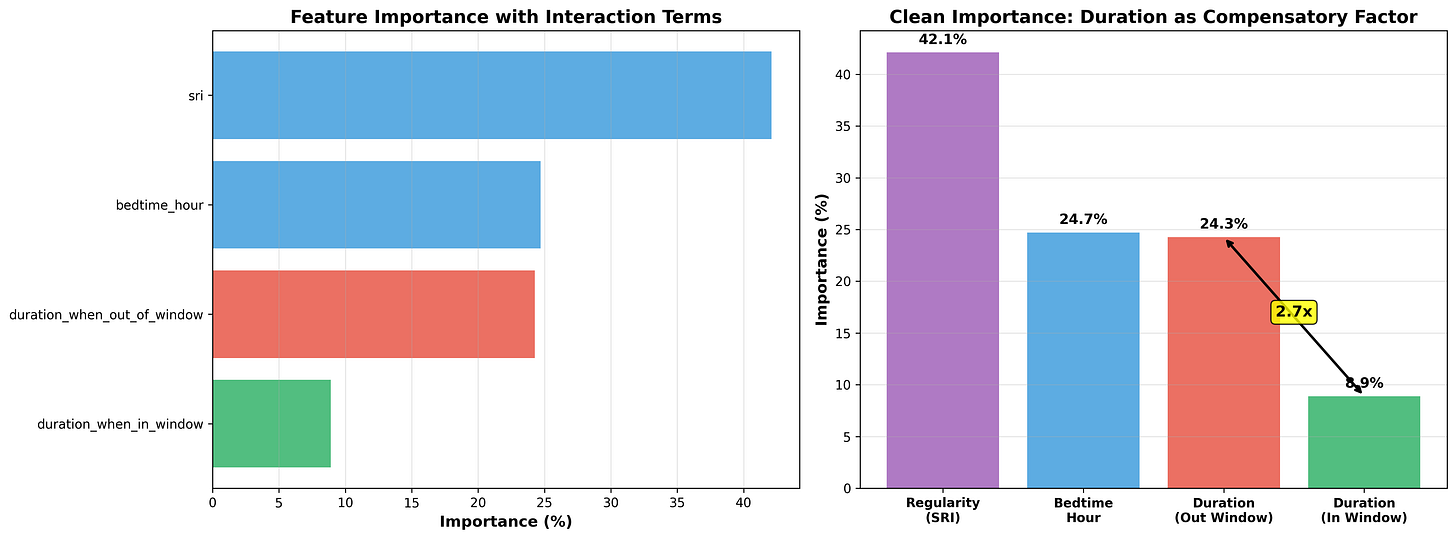

When timing was wrong, sleeping longer helped. Extra hours acted like damage control. But when timing was right, more sleep barely mattered. The returns dropped off fast.

Figure 4: Partial Dependence of Resting Heart Rate on Sleep Variables.

Regularity, timing, and duration all improve next-morning resting heart rate. Regularity has the steepest effect; timing is second; duration improves recovery mostly when timing was off.

The system wasn’t telling me to sleep more. It was telling me to sleep when it expects night to happen.

This is why people can feel terrible after 9 hours and sharp after 6.5 - duration matters, but timing determines whether those hours are actually restorative or just... time in bed.

Regularity creates the rhythm. Timing lands you on that rhythm. But there’s a third variable most people obsess over first: how many hours you actually sleep.

Duration matters - but not in the way most people think.

Finding 3: Duration Fills the Rhythm

Duration is the variable everyone chases first - and the one that matters least when structure is broken. When timing is right, 7 hours feels as good as 9. When timing is wrong, 9 hours still leaves you drained. You can't out-sleep misalignment.

Why More Hours Alone Isn’t the Answer

Sleep duration is the most intuitive lever - the one people chase first. If you're tired, you assume you need more hours. That's what I assumed too.

But in the data, duration was the weakest of the three levers.

Duration still matters. If you're already sleeping with consistent regularity and proper timing but only getting 5 hours, adding more sleep will obviously help. But if you're starting from irregular and misaligned sleep - erratic bedtimes, sleep windows that miss your biological night - chasing more hours is optimizing the wrong variable.

Duration works best when the night is already aligned. If regularity and timing are off, the extra hours don’t land in the physiology that restores you. You can sleep eight or nine hours and still wake up flat because those hours weren’t centered on your biological night.

This is why people can feel terrible after nine hours and great after six and a half. It’s not the amount. It’s where those hours fall.

Duration Helps Most When Timing Is Wrong

I wanted to see if duration had the same impact regardless of alignment, or if its effect depended on whether timing was already working.

So I split the dataset into two groups:

Aligned nights (sleep midpoint within 1 hour of HR nadir):

Duration showed almost no correlation with next-day resting heart rate

7 hours felt as recovered as 8.5 hours

The physiology had already done what it needed to do

Misaligned nights (sleep midpoint >1.5 hours from HR nadir):

Duration showed a strong correlation with next day resting heart rate

7 hours felt noticeably worse than 8.5 hours

Extra sleep partially rescued the night - but never fully

The pattern was clear: when timing was right, I didn’t need extra sleep. When timing was wrong, I needed more sleep just to feel normal.

Extra duration acted as compensation, not enhancement. It gave the system more opportunities to cycle through deep sleep and REM, but it couldn’t fully replace the benefit of sleeping in the correct circadian phase.

This is why “just get more sleep” often fails - duration can’t repair misalignment. It only softens the penalty.

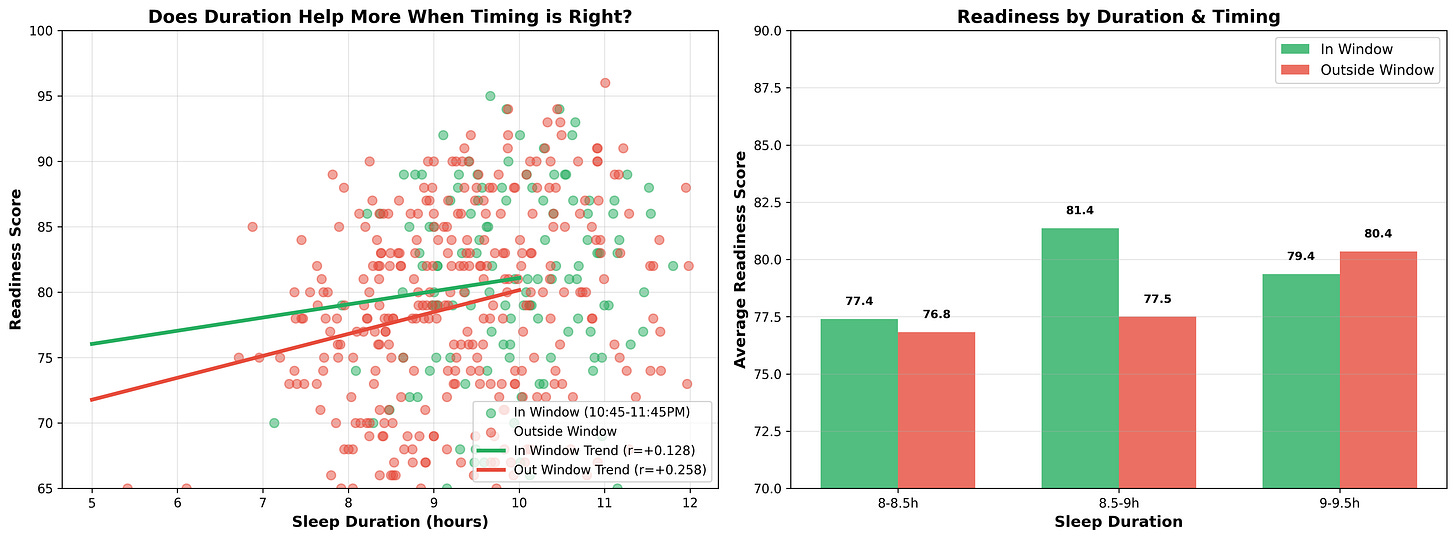

Figure 5: How Timing Affects Duration

When sleep timing is within your window, then for a given duration, you will have more energy the next day. What is interesting is in the 9-9.5h window: one explanation for this is that when we sleep outside of our window, we need to sleep longer to compensate.

How to Use Duration Intelligently

Duration still matters - but it’s the third lever, not the first. More importantly, it’s often an outcome rather than an input.

Once regularity and timing are stable, duration tends to take care of itself. A night centered on your biological night unfolds cleanly: deep sleep arrives early, REM cycles run in sequence, heart rate descends smoothly, and your body naturally wakes when restoration is complete. Sleep consolidates into 7–8 hours without forcing it.

When the structure is right, your body knows when it’s done.

When timing is imperfect - travel, schedule constraints, one-off late nights - duration becomes a fallback tool. More sleep won’t fully fix misalignment, but it softens the penalty. Think of it as damage control, not optimization.

The practical framework:

If your timing is consistently good:

Don’t force extra sleep beyond what your body naturally takes

7–8 hours in the window is usually sufficient

Trust the structure; let duration be the outcome

If your timing is occasionally off:

Add 30–90 minutes to your sleep opportunity

This won’t restore full alignment, but it softens the penalty

Think of it as a one-time buffer, not a permanent solution

If your schedule forces chronic misalignment:

Extra duration helps, but it’s a band-aid

Work on shifting your window or restructuring your schedule first

No amount of duration will solve the underlying issue

Duration isn’t the main driver of good sleep - it’s what happens when a night is already structurally sound.

How much does a small shift in regularity or timing really change things? Is this marginal optimization, or does it fundamentally alter recovery?

The data answered that question more dramatically than I expected. (See Appendix C: The Structure Determines Everything: Proof in Two Modes)

Conclusion: Build the Structure First

Once I pulled apart the data, the hierarchy became unavoidable: regularity sets the rhythm, timing lands you on the rhythm, and duration fills the space once the first two are working.

The nights that felt great weren’t accidents - they followed a predictable structural sequence. The nights that fell flat drifted outside the pattern my body had learned to expect.

For months, I tracked caffeine timing, fluid intake, meal composition, and exercise schedules, convinced that one of these would be the answer. They all mattered. But none of them worked reliably until the architecture underneath the night was aligned.

What I didn't track directly, but what the research suggests is driving a lot of this (sorry Andrew Huberman) - is light. Regularity works because it creates consistent light/dark patterns. Timing works because it places sleep in the window your light exposure has trained your body to expect. A controlled study found that light patterns can override sleep schedules entirely, shifting circadian phase by 1–2 hours in a week. I was optimizing regularity and timing; I was probably actually optimizing my light exposure without realizing it because I do have decent light interventions (blue-light protecting lenses, eye mask, dim lights, etc.)

This is the foundation. Get these three layers right, and everything else becomes clearer. Ignore them, and the smaller habits behave unpredictably.

Where This Goes Next

Once I stabilized regularity and timing, I turned back to the variables I’d been tracking: caffeine, fluids, meals, and exercise. With the foundation in place, the signals separated from the noise.

Some patterns were obvious - caffeine after 3 PM delayed my HR nadir by 20–30 minutes, even when I felt fine subjectively. Some were surprising - drinking water within 90 minutes of bedtime shifted my nadir later by 45 minutes on average.

In the next parts of this series, I’ll show you what happened when I optimized the variables everyone tries to fix first: caffeine timing, hydration protocols, meal timing, and exercise schedules.

The foundation gives you a stable system. The daily behaviors determine whether that system actually works for you.

Next: Part 2: Light, Circadian Rhythm, and the Experiment I Didn’t Know I Was Running

If regularity and timing work because they control light exposure, what happens when you control light directly? I run a 6-week experiment to find out

Key takeaways:

Sleep quality depends on structure, not just hours. Three layers matter: regularity → timing → duration. Light exposure is crucial mechanism that makes all three work.

Small structural drifts compound. Mode 1 and Mode 2 nights differed by small amounts across multiple variables - no single threshold, but the combination shifted everything.

Most people optimize backwards. They chase duration first when they should fix regularity and timing (and the light patterns that reinforce them).

Circadian rhythm is more malleable than you think. Controlled light exposure can shift your circadian phase significantly - both early and late types respond similarly.

Once structure is right, everything else (caffeine, meals, exercise) starts working predictably.

Appendix A: How to Find Your Own Sleep Window (with a Wearable)

Your optimal sleep window isn’t guessed - it’s observed. If you track sleep with a wearable (Oura, Whoop, Garmin), you already have the data. Here’s how to find it:

Step 1: Export your last 30–60 nights of data

In Oura: Settings → Account → Manage Membership → Export Data

Look for nights with complete heart rate tracking

Step 2: Filter for your best recovery nights

Sort by Readiness Score (if using Oura) or Resting Heart Rate (lower is better)

Take the top 10–15 nights where you felt genuinely recovered

Step 3: Look for the pattern

Note the sleep onset time for each of these nights

Calculate the range - they’ll typically cluster within 60–90 minutes

The center of that cluster is your biological window

Step 4: Cross-check with HR nadir timing

On your best nights, check when HR nadir occurred

Your sleep midpoint should land within 1 hour of that nadir

If it doesn’t, look for nights where midpoint and nadir were closest

If you don’t track sleep with a wearable:

Track sleep onset time and wake time manually for 2–3 weeks

Rate your recovery each morning (1–10 scale) immediately upon waking

Filter for your 8s, 9s, and 10s

The sleep onset times will cluster - that’s your window

Once you find this window, the goal isn’t to force it - it’s to land within it consistently.

Appendix B: When Your Sleep Window Conflicts with Reality

Finding your biological window doesn’t mean you can always live inside it.

Work schedules, family obligations, early meetings - real life pulls most people away from their ideal timing. If you’re a night owl whose natural window is 00:30–08:30 but you wake at 06:00 for work, you’re experiencing social jetlag: the chronic gap between when your body wants to recover and when your schedule demands.

This isn’t rare. It’s the default for most people.

Chronotype Might Be More Malleable Than We Thought

The traditional view treated chronotype as mostly fixed - determined by genetics, with only minor room for adjustment. Recent research paints a different picture.

A controlled study on circadian phase placed both early and late chronotypes on an advanced sleep schedule with controlled light exposure. Bright blue light in the morning, orange-tinted glasses in the evening (or the reverse). Both groups shifted their dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) significantly, and there was no difference in how early versus late chronotypes responded. The circadian system appears trainable regardless of your baseline preference.

Separately, a 2025 preprint (not peer reviewed) analyzing over 4,000 biological samples found that work schedules correlated with earlier circadian timing - suggesting that lifestyle and environmental factors meaningfully shape your internal clock, not just genetics.

This doesn’t mean chronotype is infinitely flexible. But for most people, those not at the genetic extremes. You likely have more room to shift than you think. The wide distribution of chronotypes in modern populations may partly reflect weak environmental signals (dim indoor light during the day, bright screens at night) rather than fixed biology.

How to Shift Your Window

Under controlled conditions, shifts of 1–2 hours per week are possible. That same controlled study on circadian phase placed both early and late chronotypes on an advanced sleep schedule with controlled light exposure. Two hours of blue light upon waking, 3 hours of orange-tinted glasses before bed. Both groups shifted their dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) by roughly 1–2 hours in one week, with no difference between chronotypes. The circadian system responds to light regardless of your baseline preference. This is fascinating stuff.

In real life, without lab-controlled lighting, shifts will definitely be slower, but the same principles apply:

Morning bright light (10,000+ lux, or direct sunlight) within 30 minutes of waking

Dim evenings - reduce screen brightness, use warm lighting after sunset

Fixed wake time - even on weekends, keep it within 30 minutes of your weekday time

Earlier meals - your gut has its own clock, and meal timing helps anchor it

Expect 15–30 minutes per week with casual compliance; faster with disciplined light control.

If Your Schedule Forces Chronic Misalignment:

Minimize variability - keep your misaligned timing as consistent as possible. An irregular misaligned schedule is worse than a consistent one.

Use free days strategically - let your body sleep closer to its natural window on weekends to reduce circadian debt, but don’t swing more than 1–2 hours or you’ll destabilize the system.

Maximize your light signals - if you can’t fully shift your window, strong morning light and dim evenings will at least reduce the gap.

Acknowledge the constraint - if you’re chronically misaligned, your recovery ceiling will be lower. That’s not a personal failure. It’s a biological constraint.

The Hard Truth

You can’t optimize your way out of fighting your circadian system every day. But for most people, the fight isn’t as fixed as it feels. Your current chronotype is partly a product of your current environment, and environments can change.

For those who do have control, or can carve out partial control, the hierarchy is your roadmap: regularity first, then timing, then duration. Shift what you can. Accept what you can’t. Build the structure around the constraints you actually have.

Appendix C: The Structure Determines Everything: Proof in Two Modes

I wanted to see if the data could reveal patterns I wasn’t consciously tracking - whether nights that felt great vs. terrible were structurally different, or just random variation.

I ran K-means clustering on 488 nights using nine features: bedtime, duration, efficiency, sleep regularity index, morning resting heart rate, HRV, deep sleep percentage, REM percentage, and alignment.

The algorithm found exactly two clusters. What this tells me is you don’t have one sleep pattern with natural variation. You have two fundamentally different modes. Note that these are averages!

Mode 1: High-Recovery Nights (59.8% of nights)

Morning RHR: 55 bpm

Bedtime: 23:48 (std: 64 min)

Duration: 9h 28m

Sleep Regularity Index: 93.8%

Sleep Efficiency: 84.5%

Alignment: tight (midpoint close to HR nadir)

Mode 2: Low-Recovery Nights (40.2% of nights)

Morning RHR: 64.5 bpm

Bedtime: 00:03 (std: 121 min)

Duration: 9h 05m

Sleep Regularity Index: 91.2%

Sleep Efficiency: 82.0%

Alignment: loose (midpoint drifted from HR nadir)

Look at what separates them:

15-minute bedtime shift (23:48 vs 00:03)

2.6% drop in regularity (93.8% vs 91.2%)

23 minutes less sleep (9h 28m vs 9h 05m)

Those small structural differences corresponded to a 10 bpm difference in next-morning resting heart rate (Cohen’s d = 1.8, p < 0.001).

What This Means (and Doesn’t Mean)

Here’s what surprised me: bedtime alone explains almost nothing. The direct correlation between bedtime and RHR was r = 0.07 - just 0.4% of variance, not even statistically significant.

More telling: 41% of my Mode 1 nights had bedtimes later than the Mode 2 average. The modes overlap almost completely in bedtime range. The 15-minute difference is a statistical artifact of averaging two overlapping distributions - not a threshold.

What the clustering found wasn’t a bedtime cutoff. It found nights where multiple small things drifted together: timing shifted slightly, regularity dropped slightly, duration fell slightly. No single variable crossed a line. The combination flipped the physiology.

Why a 60-Minute Window Works

If bedtime doesn’t predict recovery, why recommend a window at all?

Because the window builds regularity, not timing precision.

Mode 1 nights had bedtime variability of ~64 minutes. Mode 2 nights scattered across 121 minutes. The good cluster is consistent. The bad cluster is chaotic.

The 60-minute window keeps you landing consistently, which builds the high regularity (93.8%) that characterizes Mode 1. You can recover well at 00:30 if the structure holds, or poorly at 23:00 if it’s drifting.

The structure determines the mode. The mode determines how you feel.

The hierarchy you're describing here—regularity, timing, duration—maps perfectly onto what chronobiologists call the "circadian stability index." Research from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Study found that consistency of sleep timing predicted subjective sleep quality better than total sleep duration. The shift work population faces a unique challenge: their "biological night" keeps trying to reassert itself even when they're forcing an inverted schedule. The key insight for shift workers isn't achieving perfect alignment (impossible for most), but rather minimizing the variability in misalignment. Consistency of when you're awake relative to your circadian phase matters more than the phase itself. Your HR nadir metric is brilliant—it's essentially a DIY version of DLMO testing without the melatonin assays.